I’m writing this whilst sitting on a magic carpet. It doesn’t match our living room decor, is too short to cover the whole floor, and does nothing for the feng shui of the place. Yet this faded Berber rug has lain here for years serving as both a memory and a lesson.

It was our very first purchase secured through the medium of haggling, and I’m not too proud to admit our bargaining attempts were beyond pathetic. Hubbie and I had innocently wandered down to the Marrakech tanneries, truly believing we would be leaving with just photographs. Even the directions were free, provided by a pleasant lad who simply wanted to practise his English as he escorted us deeper into the labyrinthine medina. We should have known better, but wide eyed and ignorant we trotted along blissfully unaware of the unfolding charade. The tannery pits were fascinating, the workers mesmerizing and the smell astounding, but it was the factory that really stopped us in our tracks. The owner kindly offered us mint tea whilst we admired his legions of leather and stacks of carpets and made suitable murmurs of appreciation.

Before long we were unable to just walk away, totally incapable of shaking off the cumbersome ball and chain of English politeness. Half an hour later we emerged armed with a rug we didn’t want and a chasm in our bank account we hadn’t anticipated. Feeling rather stupid we reminded ourselves all was not lost. The rug was real cactus silk because it didn’t go up in flames when the vendor threatened it with his lighter. So at least if our house burns down we’ll still have something to sit on.

Several years and haggles later hubbie and I now consider ourselves masters in the art of hard bargaining, having perfected our skills in markets across North Africa and Asia. We’ve become smug basking in the glory of each cheap souvenir achieved, yet we’ve also discovered the art of tact, and know when it’s okay to not haggle and still come away with our heads held high.

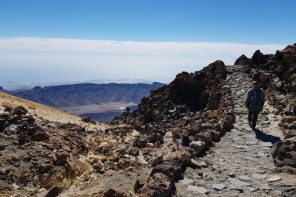

The cost of living in Indonesia is even cheaper than Morocco. Battering down prices here was merely an exercise in experience ownership and personal pride. It certainly would not dictate the quality of noodles we could afford for dinner that evening. One scorching afternoon we found ourselves wandering the slopes of the Mount Merapi, the lonely volcano that looms magnificent over the vast plains of eastern Java.

We stopped amidst the rubble of what had recently been the highest village on the mountain, gawping at the merciless fingers of grey lava that gripped the mountainside, reaching down into the valleys having devoured everything in their path. Charred trees lay scattered like matchsticks over the barren wasteland, with freshly dug graves standing like forlorn sentinels keeping watch over the desolation.

It was a few months since the October 2010 eruptions and villagers were returning to piece their lives back together. They were living in tiny make-shift shelters and optimistically selling dubious-looking bottled drinks in hopeful anticipation of thirsty visitors. We spoke to several and marvelled at their stubborn determination to return to the danger zone. They knew that living in the shadow of one of the world’s most active volcanoes would always be risky, but the land has been theirs for generations and nothing would take it away from them. Not even a volcano that with its latest effort killed hundreds of people.

Driving through villages further down the slopes we’d noticed several bill boards with faded pictures of an elderly man. The villagers told us with sad smiles that this was Mbah Maridjan, appointed by the Sultan of Yogyakarta as ‘gatekeeper’ of the volcano to manage Mount Merapi ‘s vengeful spirits. He took his job seriously and refused to evacuate during the eruptions, explaining to officials that he would stay and try to pacify the angry gods. Unfortunately science outwitted spirituality and Maridjan perished, along with many of his followers who were bound by Javanese tradition to obey their spiritual leader.

In what was left of the village we quickly took a few photos, feeling like intruders in our fascination, before returning past the subdued little shacks and their forlornly displayed wares. There is a time and a place for an overload of e-numbers, and it wasn’t here, but we nonetheless purchased several bottles of fluorescent fizzy pop from one family, before stopping a few metres further on to admire a bench laden with household articles and souvenirs ingeniously fashioned out of lava.

After much debate and friendly chatter with the family, we decided on a model of Borobudur, and pestle and mortar. Not because we fancied sulphur flavoured herbs in our cooking, but because I thought it would be a good addition to our souvenir collection, kind of matching the rug but with a different sentiment and lesson behind it. Hubbie groaned inwardly, correctly anticipating he’d be the one carrying it down the mountain.

The mother asked for 50,000 rupiah (less than £3), clearly expecting us to negotiate, yet we realised what a huge difference a little money would make to these villagers and immediately agreed on her asking price. The grandmother tried to force us to bargain, but we could tell by ill-concealed grins that this sale would make their week. In the event we didn’t actually have the correct change and instead gave 100,000 rupiah, trying desperately not to feel arrogantly bountiful in our generosity.

The tears, smiles and grateful hugs that followed were worth every penny, and to all those sceptics who will lecture on the economics of such actions and the impact this may have on future tourists, I say that I have no doubt the family will in remain honest and humble. Sure, perhaps they snared my sympathy vote with relative ease, but at least I have a home where I can display my new wares.

Sometimes the experience and the opportunity to make a difference to someone’s life is worth far more than the souvenir that is just going to end up on a shelf collecting dust.

This is a lovely post! I’ve been tempted to do overpay a few times while travelling but haven’t wanted to offend. I often remind myself that a pound or two is nothing to me but makes the world of difference to some people. I think travellers should remember that and help when they can, although not in areas where tourist prices are deliberately hiked up and no locals are suffering.

Thanks Dannielle 🙂 It’s all about getting the right balance isn’t it.

Love your writing style and love that you got it so right

Ah, thanks 🙂

When you meet honest, hard-working people trying to put food on the table…I try to forget I am cheap.

We do sometimes have to remember it’s not all about our own pride.

Heather, I enjoyed reading this article, and I know that you will forever feel good about this exchange.

Thanks Corinne, I guess it’s not wrong to feel good about doing something worthwhile!

Great reminder that undercutting the price is not always to best deal.

I really appreciate this post so much. Great writing 🙂 I completely understand what you are talking about. In such third world countries, tourists can be so aggressive with the haggling just to make a point of it and just to see how low they can get the vendor to drop their price, as you say, for “pride.” But you’re so right how the difference means absolutely nothing to the tourist but can mean everything to the vendor.

Thanks! It really is all about striking the right balance isn’t it.

I really liked and enjoyed this post. Good writing and also an important issue that I can relate to so much.

That was one of the most gorgeous articles I have read in a while. I can completely relate to the over-zealous need on the part of tourists and travelers to dismiss the opportunity to not haggle in favor of always seeking to get a deal. Good for you on recognizing and acting on the the good fortune of being born in one place over another. The people around Merapi have had it rough; I was there in 2010 when it erupted and I was amazed at how well they and the people of Yogya handled it.

Ah, thanks Tim. I wasn’t sure whether I’d get shot down for going against what we’re supposed to do as tourists (i.e. haggle hard) but it does pay to remember we’re rather fortunate with our place in world society. One thing I do know, we wouldn’t handle it anywhere near as well as the people of Yogya do time and time again!